Feature: We're Not Always Just One or the Other

The new all-gender house will reflect “the breadth and complexity of the human experience”

Michael Matros

This fall, a new student house will open at St. Paul’s School in one of the white clapboard buildings on Jerome Ridge, former home to deans and teaching fellows. By then, it will have a more formal name, but now everyone just calls it by its purpose; the all-gender house. Administrators emphasize that St. Paul’s is not on the path to establishing the kind of co-ed dorm now taken for granted on most college campuses. But, they say, just as at sister schools – Andover, Exeter, and others – the SPS community has come to realize that gender lies on a spectrum much like other facets of human existence, a spectrum that includes gradations between traditional female and male identities. The creation of the all-gender house recognizes this understanding.

“I personally believe that the notion of gender and gender identity does not lie on a binary scale, that it is exclusively one or the other,” says Interim Rector Amy Richards. “So, if you believe that, and you look out across the landscape of human experience, you recognize that so many structures that are human-built are designed around a binary blueprint and therefore don’t fully embrace the diversity that is humankind.

“I think there is a fundamental benefit in the School’s embracing more of the middle of this gender spectrum.” In its pilot year, the new house will welcome up to nine students. Some may identify as transgender or gender-nonconforming. Others will be “allies,” or advocates of those students. A few others, says Vice Rector for School Life Dr. Theresa Ferns ’84, simply may not feel comfortable in spaces that are exclusively male or female, with a perceived level in those environments of hyper-masculinity or -femininity. Establishing the new house, Dr. Ferns says, “underscores the Episcopal value of ‘radical welcome’ – to be open to everyone, to create the most welcoming environment no matter how students identify.”

The effort, says Dean of Admission Scott Bohan ’94, “reflects the value of St. Paul’s School as being an inclusive community, something we talk about all the time. We’ve got nice kids, they’re good to each other, we’ve got spaces and opportunities for kids to be kind, and when families come and visit the School, having one more example of how inclusive and welcoming we are is another thing that will help us in Admission tell the St. Paul’s School story.”

“Some parents who’ve visited other schools with all-gender housing have asked about this,” Bohan adds, “and they’re excited to hear we’re going down this road.” This initiative may seem part of a brave new world, but, as Richards says, “Part of what I have observed is a certain matter-of-factness to this.”

“Among the student population, for example,” Richards explains, “there’s a little bit of shoulder-shrugging. In other words, it does not seem particularly monumental or notable, and I think part of it is, for this generation of young people and for the young people who will follow them to St. Paul’s, the notion that gender is something other than binary seems very matter of fact.” When the School formed the Gender Equity Task Force in 2017, one of its charges was to consider the possibility of creating an all-gender house. Along with consulting with peer schools about their experiences in establishing all-gender dormitories on their campuses, the group’s members spent time discussing whether current student housing policies reflected the School’s most basic premise and promise – that of kindness.

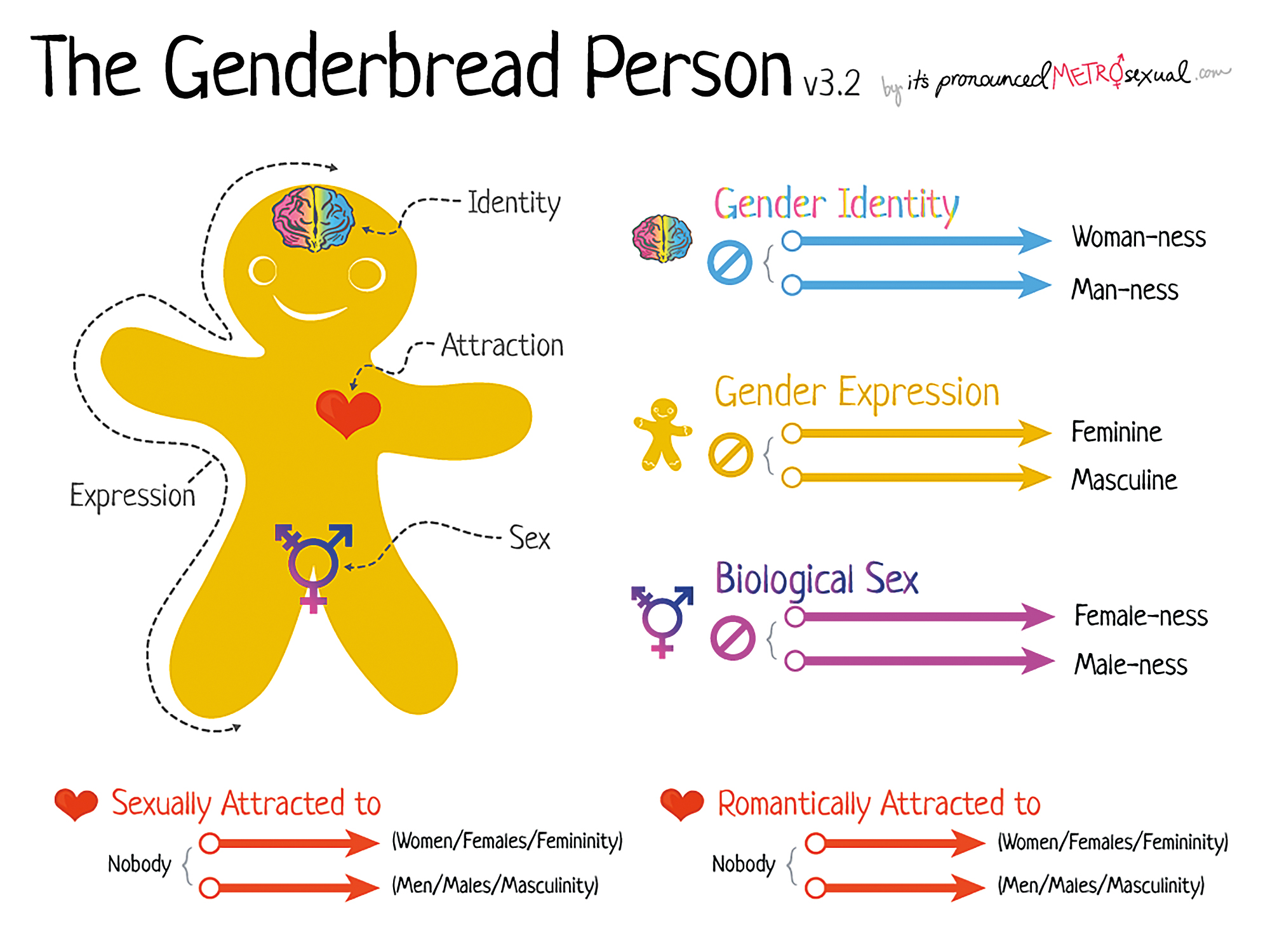

This “Gingerbread Person” graphic is used within the LINC curriculum to help convey an understanding of gender vs. sex, as a basis to then explore the terms “cisgender,” “transgender,” “nonbinary,” and others.

Dr. Ferns presented the recommendations of the task force to SPS trustees at the board’s January 2019 meeting, with the conclusion that “our current binary residential system does not meet the School’s commitment to inclusivity and ‘radical welcome,’ in which every community member is supported and valued for their authentic selves.” At the board meeting, Dr. Ferns described the process that led the task force members toward their recommendation, which included a visit to Phillips Exeter, where they spoke with students living in the Academy’s two all-gender houses, the first of which opened in 2017. A transgender faculty member from Exeter then came to St. Paul’s for a presentation to the faculty.

Also persuasive was a video produced by Exeter students to describe all-gender living at the school. “The Academy,” says Exeter Director of Student Activities Joanne Limbo in the video, “wants people to bring their whole selves here and not leave someone behind, not have to hide anything....A safe space is critical for a student to thrive where they’re in school.” In addition to consultation with sister schools, additional research and education for the SPS Gender Equity Task Force included house meetings, student focus groups, and entries in the LINC (Living in Community) curriculum, the School’s residential-learning program. And, in December 2018, the task force circulated a survey to all students to assess support for an all-gender house and to ask about their interest in living in such a house. With 90 percent of students participating, 62 percent indicated support for the house, with 11 percent opposed. Some 65 students reported interest in living in an all-gender dorm.

“I think we’re trying to make a statement as a school,” a student in one of the focus groups observed, “and, if we’re trying to push for inclusivity, we can’t continue to have dorms that do not include people.”

“Go for it over the summer,” another student wrote. “Just do it – rip off the Band-Aid. I know you want to build a strong base [of support], but the more you wait, the more kids get hurt because they don’t have that safe space on campus.” With the trustees, Interim Rector Richards says, “the discussion was thoughtful and responsive and pointed the School in the very obvious direction of taking the next step. There wasn’t anyone in the room who said maybe we need to tap the brakes on this a little bit and get more information.”

A LINC Day devoted to the LGBTQ+ community celebrated the past and sought to cultivate empathy.

Recognizing nonbinary identity as more than a theoretical civil rights issue became immediate just days before Graduation 2017. At that time, a gender nonconforming Sixth Former considered the boy-girl procession that opens the ceremony and asked, “Where do I belong?” Conversations ensued among Vice Rector Ferns, then-Rector Michael Hirschfeld ’85, and other adults, but mostly among students, about whether it was time to change a longstanding tradition. “The kids who felt strongly that we shouldn’t change it,” recalls Dr. Ferns, “finally said, ‘wait, if everyone doesn’t have a place to be I think we need to change it.’ It was a good example of student engagement, of their participation in civil discourse, and an ability to come to a conclusion, a consensus about what was right.”

Since that June day, Sixth Formers now walk in the procession side-by-side, according to the alphabet and not their gender identity. Yes, still in dresses and jackets, but this year with the same red carnation pinned on – no longer the distinction of boys’ white boutonnière or girls’ red corsage with baby’s breath. According to its name and charter, the Gender Equity Task Force addresses issues other than fair housing, but it has directed a primary focus on the need to recognize the range of student gender identities. Dean of Students Aaron Marsh ’97 is working with the group “to look at everything from language in the handbook to certain practices, traditions, the dress code – certain elements of which have changed this year.”

“We had a dress code for boys and a dress code for girls,” Bohan adds. “Now we have a dress code for students. It allows for students of various identities or various socioeconomic backgrounds to feel comfortable, whether in class or at the more formal events, such as Seated Meal or Evensong.”

“What’s good in all these decisions,” Bohan continues, “has been that the ‘how’ and the ‘what’ has continued to be evaluated, but the ‘why’ has stayed pretty consistent. We want to be more inclusive; we want to be the kind of community where everyone can be comfortable. It’s a guiding principle for our decision-making.” The graduation procession decision, says Marsh, “is a great example of how a traditional practice could marginalize a great student. There are lots of things we’ve done for a long time that have been embedded but are not inclusive. These changes are really important in a place where every kid should feel valued, accepted – that this is their home and their school.”

“Some alumni from the past didn’t understand how these practices may have affected their peers,” continues Marsh, who attended the School in the mid-nineties. “I’m sure there were peers of mine who were made to feel not welcome in this community. Parts of this place made me feel not welcome.”

“We’re not just changing things to change things,” insists Bohan, “not just reacting to student concerns. We listen and engage in appropriate dialogue and conversations, reflection, and then we land maybe in the same place but with a better understanding of why we’re there, or we [may] land in a different place and we feel good about that.” Fairness, says Bohan, is the key to decision-making. And it helps, he points out, that alumni such as himself are involved in the process. When some alumni have called about changes in Seated Meal traditions, he asks them, “Do you remember the couches and who was allowed to sit on them? Do you remember the blue rug that only certain kids could stand on and look at the girls parading by? Yeah? Well, none of that’s good.”

“What’s telling for me,” says Dr. Ferns, “is that the students have raised their voices, and I think they’re feeling heard. So we continually have students bring forward their lived experience here at the School and ask us to continue to look at things. It doesn’t mean we immediately change things. We have a process.” The process for instituting the new space has been, and continues to be, in discussion. How to name the house may or may not be one of the easier decisions, but other issues are more immediate – what rules, intervisitation and others, will be the most fair and effective? Should the new house affiliate itself with a larger house for events such as the Fiske Cup and hosting Rectory open houses? And, at the top of the list, how should the first year’s residents be chosen from what is likely to be a fairly significant number of applicants.

“We’ll make decisions based on the pool of students who are applying,” Dr. Ferns says. In a February letter to SPS parents, Interim Rector Richards explained that “priority will be given to those for whom this option will be most beneficial. Parent permission to live in the house will be required as a final step in the application process.”

“Surprisingly,” Richards says, “I haven’t heard from that many parents beyond a few basic questions, asking about the timeline, asking if we had already identified what building was to be converted, and a few clarifying questions. At least one parent indicated their child was interested in applying for housing in the all-gender dorm.” Richards explains that the initiative addresses what is partly a civil rights issue but is primarily educational. “Students having contact with the breadth and complexity of the human experience,” she says, “results in better prepared, more knowledgeable, more empathetic servant leaders that we aspire to graduate out into the world.”