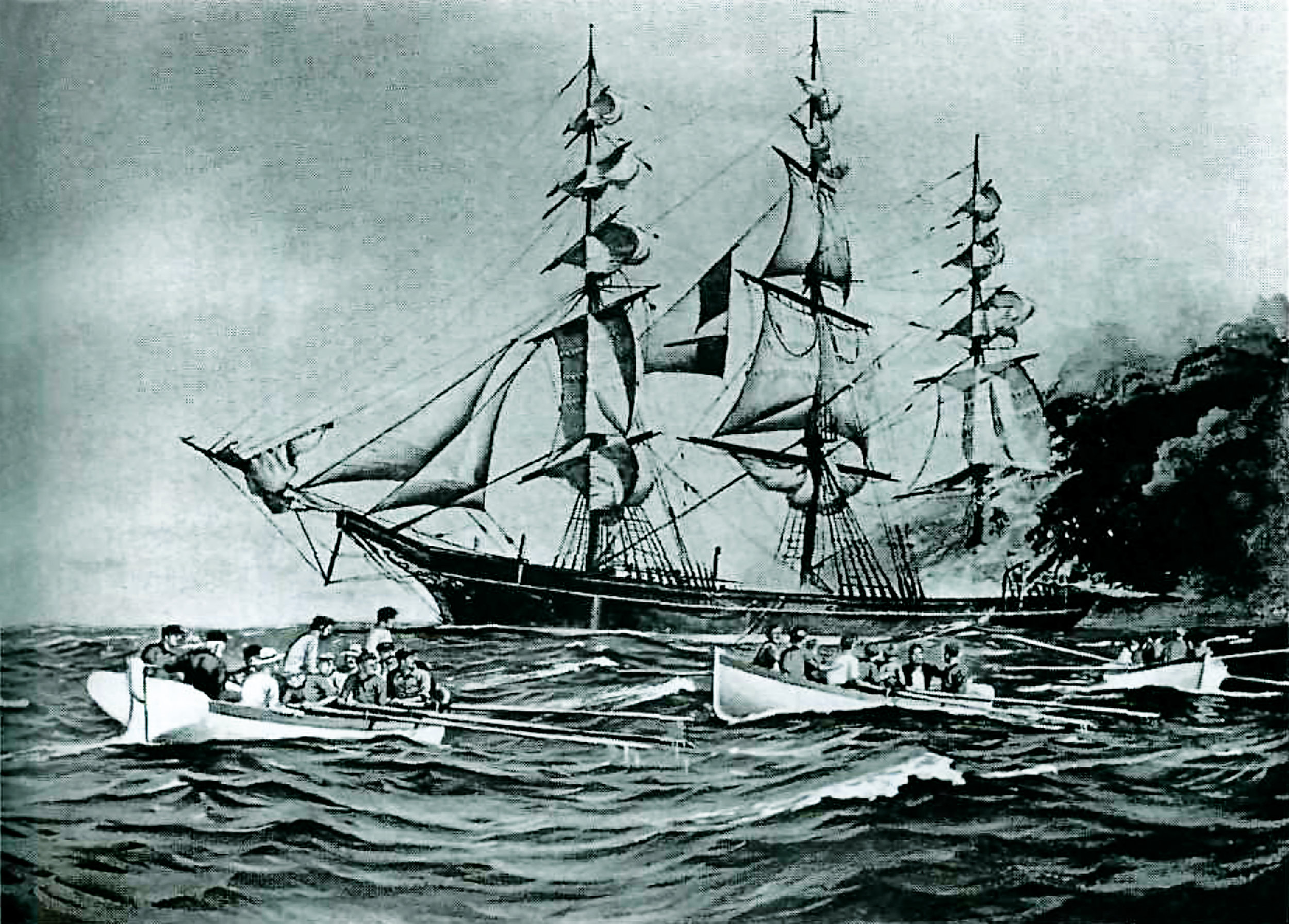

Nostalgia: Last Voyage of the Hornet, the saga of Rector Henry Ferguson's survival at sea

Last Voyage of the Hornet, First Voyage of a Leader - Long before he became the Third Rector of St. Paul’s School, a teenage Henry Ferguson demonstrated resilience as a survivor of a legendary shipwreck that made Mark Twain famous.

Long before he shepherded St. Paul’s into the next century, Third Rector Henry Ferguson (Form of 1864) was already internationally famous. After surviving a shipwreck with his brother, Samuel (SPS 1853), he traveled 4,300 miles in an open boat, an astounding feat that surpassed the more famous voyage of Captain Bligh.

In School history, Dr. Ferguson is well known for introducing progressive ideas to a traditional institution at the turn of the 20th century. In 1906, he accepted the position of Rector on the condition that his term be limited to five years. During his first year, he refused to accept any pay. In subsequent years, Dr. Ferguson put his salary into a savings account. When he retired, he used the savings to create the Rector’s Collateral Fund, a pool of money available to future Rectors to use at their discretion.

Dr. Ferguson was practical and methodical, reorganizing methods for keeping records and then turning his attention to updating outmoded buildings. He found solutions to longstanding quarrels among the faculty and introduced a more progressive curriculum. Discipline was, perhaps, Dr. Ferguson’s weakest point; he enjoyed life and had a forgiving nature. Nevertheless, his smiling benevolence resulted in greater esprit de corps and fewer behavioral problems.

It was January 1866, when Dr. Ferguson and his 27-year-old brother set off for California on a clipper ship from New York City, set to travel around Cape Horn. They boarded the Hornet, one of the largest and finest clippers of her day, and were soon on their way to sunny California. Henry, a 17-year-old sophomore at Trinity College, had agreed to accompany his older brother, who was sick with tuberculosis and hoping the move to a warm, dry climate might mitigate his illness.

Both Fergusons kept daily travel logs. On January 14, 1866, Henry wrote, “very comfortably situated and we think we will get along very well. We like the captain and mate, what we have seen of them, very well.”

Josiah Mitchell, a clipper captain from Freeport, Maine, with nearly 40 years’ experience at sea, was equally glad of their company. The brothers dined with the captain every evening and played cards in his cabin. The Fergusons found life at sea fascinating; their diaries record sightings of whales and flying fish. They watched the north star set as southern constellations rose, and learned some navigation. “Captain lent Henry an old, but first-rate, quadrant, which he is to take charge of and practice with daily,” wrote Samuel. Henry also befriended many of the crewmen, especially Fred Clough, 20.

They made their way up the west coast of Chile and the winds began to fade as they reached the doldrums, a region of dead air a thousand miles wide that spans the equator. Captain Mitchell kept the crew busy doing ship’s maintenance. On May 3, he ordered the first mate, Sam Hardy, to fetch some varnish. Hardy went below with a candle to light his way through the dark ship’s hold. In the hot, stagnant air of the hold, the candle ignited fumes from the varnish. In no time, the flames had spread to the highly flammable cargo of kerosene, coal, and candles.

Charles Rosner painting of the Hornet on fire.

Hardy leapt on deck, calling “Fire!” The crew sprang to action, but the first kerosene barrel exploded, sending up a geyser of flame that ignited a staysail, 15 feet above the deck. From there, the flames ran along the dry manila lines and freshly tarred rigging until the Hornet was engulfed in flame from the depth of the hold to the sky sails, 200 feet above. Only 30 minutes after the vapors ignited, the captain gave the order to abandon ship.

Thirty-three men scrambled for three small boats. They salvaged nothing but three days’ rations and some navigational equipment. The Hornet burned for 24 hours. The crew stayed close by, hoping a passing ship would see the flames. Nobody came.

The Pacific is vast, covering more area than all the continents combined. And, in 1866, it was still poorly charted and sparsely traveled. Captain Mitchell was at a loss, writing, “Where are we to go, in God’s name, with this small lot of stores?”

A page from Samuel Ferguson’s journal writen on the day the Hornet burned.

Henry was calm and probably in denial: “Ship sank at 5 a.m. and we are now alone on the ocean....We stayed near the ship till she sank and are now heading NxE for some islands….Two crackers and a pint of water is our allowance. Sun is terribly hot and blistering. All in pretty good spirits.”

The three boats rocked helplessly in the equatorial sun more than a thousand miles west of the Galapagos. On short rations, their food might be stretched to last for 10 days, but the small, jury-rigged sails were all but useless in the doldrums.

For the young men, boredom was the worst enemy. Confined in a 21-foot boat with 14 other men and going nowhere, Henry’s normally exuberant and detailed entries changed. For six days, he wrote only a single word each day: “doldrums.” Depression was understandable and temporary. Eventually, a fresh breeze restored his courage and Henry reemerged vital and determined.

The diaries show both Fergusons to be psychologically resilient. Through tormenting hunger and thirst, in scorching sun and drenching downpours, despite one disappointment after another, they are persistently courageous and grateful for small blessings.

Perhaps experiences at SPS gave them good grounding. After three weeks in the cramped boats, Henry longed for spiritual advice and consolation, referencing First Rector Henry Coit, “I would give anything for talk with Dr. Coit.” Inevitably, discord arose. The three boats separated. Unfavorable winds and inaccurate charts caused the captain to miss islands or aim for those that did not exist. The disappointed crew grew impatient and began to distrust the captain’s navigational skills. There was talk of murder and mutiny.

Fourteen-year-old sailor Jimmy Cox whispered a midnight warning to Henry that probably saved his life. Henry passed the information to his brother in a note scratched on the back page of his diary: “Cox told me last night that there is getting to be a good deal of ugly talk among the men against the captain and us aft....There is nothing definite yet as I understand him, but starving men are the same as maniacs. It would be well to keep a watch on your pistol.” Informed of a possible mutiny, Captain Mitchell and the Fergusons remained constantly on alert, sleeping only in shifts.

A Harper’s Weekend illustration of the fire to go with Mark Twain’s article.

After 37 days, they finished the last of their provisions, a single can of soup divided among 15 men. Some talked of eating the first to die, while others argued for drawing straws to choose a sacrifice. The very idea horrified Henry and yet, at times, he questioned his own resolve. “Ate the rind of the ham-bone and have the bone and greasy cloth to eat tomorrow. God send us some birds or fish and let us not perish of hunger or be brought to the dreadful alternative of human flesh! As I feel now, I don’t think anything could persuade me, but can’t tell what you will do when reduced by hunger and crazy.”

Six more days passed without any food, then they ran out of water. On the 43rd day, the famished sailors demanded to draw straws. No sacrifice took place because they sighted Hawaii and managed to come ashore in the little village of Laupāhoehoe. Gaunt, ghostly, and too weak to stand, they were cared for by the locals.

Henry was young and recovered quickly, but Samuel did not. He weighed just 84 pounds and was weakened by tuberculosis. Henry refused to acknowledge this, but Captain Mitchell wrote that he would be surprised if Samuel lived the year out. Coincidentally, a frustrated author named Samuel Clemens was in Hawaii, writing travel stories for a newspaper and dreaming of bigger things. When he learned shipwreck survivors had washed ashore after 43 days at sea, Clemens recognized the story as “literary gold.” He interviewed the crew, stayed up all night preparing his copy, and delivered it the following day to a ship bound for San Francisco. The story created a sensation and was quickly telegraphed across America and around the world, bringing Clemens the fame he sought as Mark Twain.

Returning to California, Clemens made sure he was on the same ship as Captain Mitchell and the Ferguson brothers so he could gather further details. The brothers even allowed him to copy their diaries on the condition that names be omitted from any publication in order to protect reputations. Clemens broke that promise when his article in Harper’s Magazine reprinted long segments of the unedited diaries.

The title page of Henry Ferguson’s journal.

Samuel Ferguson died soon after reaching San Francisco. Despite the physical and mental shock of his ordeal, Henry returned immediately to Trinity College and graduated with his class in 1868.

Thirty years later, Mark Twain began work on his memoirs. The first installment, entitled My Debut as a Literary Person, was published in The Century magazine. The article retold the tale of the Hornet, including portions of Samuel’s diary. This prompted Henry to write Twain with a tactful request: “If it is likely to be published in book form, can you not suppress all the names that are mentioned in any unfavorable way?”

Twain’s reply was testy, but he complied with Henry’s request. One who had been harmed by the publicity was Henry’s old friend, Fred Clough. Twain’s original article branded Clough as a cannibal and ruined his reputation.

Fifty years after the Hornet went down, Henry learned that Fred Clough’s life was in shambles. He had lost his home and become an alcoholic, drifting from one San Francisco boarding house to another. Although they had not met in half a century, Henry granted Fred a lifetime annuity for his support. Henry Ferguson married and had four children. Eventually, he became a clergyman and professor of history and political science at Trinity College. He was widely revered as a scholar, a peacemaker, and – always – a man of God.

Details of the adventures of Henry and Samuel Ferguson can be found in Last Voyage of the Hornet by Kristin Krause.